From my own observations (and even my own experience pre-SAR days) most people want to understand more about navigation techniques, but they don’t know where to go to learn it. Or they’ve tried to learn it and it just doesn’t seem to “stick” for very long afterwards.

And with the advent of modern apps and GPS units, are map and compass skills even necessary? The answer to that question is a resounding YES. You should always carry a map and compass (and even more importantly, know how to use them).

The good news is that map and compass skills are only one part of many in your navigational tool kit, albeit an important one. From my standpoint and experience, navigation is best understood and practiced successfully when you incorporate the following into your hikes:

- Map and compass skills

- Navigational apps or GPS units

- Dead reckoning techniques

- Environmental navigation techniques

Map and Compass Skills

Nowadays, you can practically learn how to build a rocket ship on YouTube, and I love finding a knowledgeable and respected channel for all sorts of skills. But here’s the thing, learning map and compass navigation is one of those tricky beasts that requires more than watching a screen inside. You’ve gotta get outside in the field and practice your skills, especially as you learn them.

And I get it. Without someone standing beside you showing you how to put “Red Fred in his shed” (that’s a really helpful way to remember how to follow a bearing, by the way), you may feel like its useless to even try. I used to think the same thing. Even with my search and rescue training, I still felt lost a few days after packing my head full of navigation knowledge.

Then I stumbled on a book called Wilderness Navigation: Finding Your Way Using Map, Compass, Altimeter, and GPS at my local library. I checked it out, went up to the top of my favorite local balds, and sat there with my map, compass, and this book, practicing techniques as I read about them…over and over and over (but to be clear, I didn’t wander off into the woods and “hope for the best” with my new skills–I stuck to familiar territory on a bald mountain very familiar to me, and I practiced in an area with a small radius!).

Guess what? It started to click in a logical way versus just memorizing facts that I’d soon forget. I probably had to read the same chapter three times and practice the skills triple that amount in the field before it really sunk in, but it did. Public library for the win!

Key Takeaway: Learning map and compass navigation skills is best learned in the field and at your brain’s unique pace for fully understanding the basics and beyond. Practice makes perfect and it’s a perishable skill, so don’t forget to practice it every so often.

I highly recommend teaching your kids navigation basics too! Hiking off trail in Death Valley National Park to Panamint Sand Dunes provided great practice for mine!

**If you’d like a recommendation for a basic but sufficient compass made by a well-respected brand (Suunto), especially if you’re just starting to learn navigation,I recommend this one.

Phone Navigation Apps

Some purists scoff at the idea of using a GPS unit or a navigational app on a smart phone. I’m not in that camp, but I am also not in the camp that espouses replacing the map and compass in your pack with these things. Technology fails, phones are easy to drop in streams (ask me how I know), and aside from that, many experts think that using technology to navigate can work against us if we’re not careful.

In 2016, the British Mountaineering Council published an article that stated, ““People using GPS for navigation just aren’t building a mental map in the same way you do in traditional map and compass navigation, where you are constantly relating the map to the terrain around you. That means if the technology fails for whatever reason, you are going to be a lot more lost than you would have been if you were using a map.”

I agree wholeheartedly with this statement. While I fully support this technology to complement map and compass skills, it’s not meant to replace them.

That being said, I use Gaia GPS, a navigational app, frequently. My map and compass are always with me and I don’t just bury them in the bottom of my backpack, but I love Gaia and all the perks it affords me on a hike.

The ways I use Gaia are as follows:

Route Creation: Before my hike, I log into my Gaia account on my computer and create a route of the hike I’m taking. This provides a quick reference for mileage, elevation gain and loss, etc. and gives me a general sense of my ability to hike it safely and within the amount of time I have (sometimes, I also use a website called Caltopo for this purpose too, but that’s another discussion for another time).

I send a link of this route to my husband and a SAR teammate/friend, so two people know where I am and when I’m expected to return home.

Quick reference on the trail: It’s much easier to pull my phone out of my pocket and look at the map on Gaia, to double check where I’m supposed to turn at a known trail junction. Or sometimes, I’ll just want to see how far I’ve hiked and if it aligns with my “dead reckoning” guesses (we’ll get to dead reckoning soon).

Record of my hikes: By using Gaia to lay a track while I hike, it provides me with a record of my hikes that I can easily store and reference and even share with other people in the future, who might want to hike the same route. Also, if you’re working on a hiking challenge, such as the Smokies 900, it’s a great way to keep track of what you’ve hiked and when you hiked it.

Off Trail Insurance: If I’m hiking an off-trail route either for SAR or for fun, I really appreciate the “security blanket” a navigational app affords me. It’s also great if I have someone else’s GPX file for an off-trail route I’m trying to safely emulate.

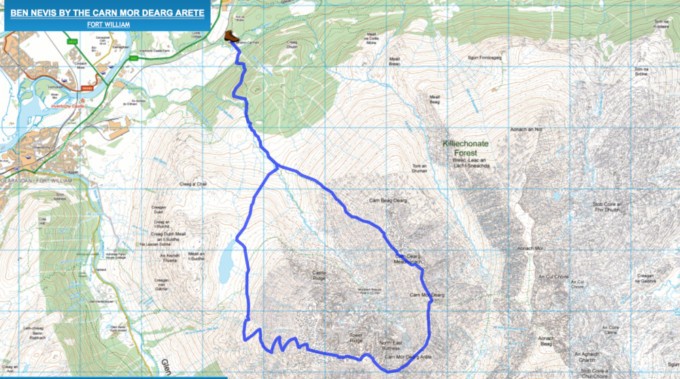

When I hiked a mostly off-trail route to the highest point in the United Kingdom, Ben Nevis, I downloaded a GPX file into my Gaia app to confirm I was roughly following the recommended route during the hike.

If I’m in a situation where I need clarification of where I am on a route or guidance on which direction to head, I first resort to using my map and compass skills. Then I verify my educated guess with Gaia. I don’t automatically use my app to bail me out.

The one exception would be if you’re in a threatening situation that you need to remove yourself from quickly, in which case it’s fine to jump straight to the quickest and easiest reference, which is probably your digital navigation method!

Key Takeaway: Digital technology such as apps and/or GPS units are incredibly useful tools in the backcountry, but they should be used as your backup source of navigation, not your primary method.

As a side note, I’m able to offer my readers a nice discount off a Gaia GPS subscription and I can’t say enough good things about this app. I use the Premium version because I like the added features and functionality it provides (like the National Geographic map overlay), but the basic membership is fine for most people’s needs.

Also, if you’d like to watch a video tutorial of how I use Gaia for my own hikes and hear more about all the robust functionality of this app, you can watch a Facebook Live I did on the topic right here.

Dead Reckoning Techniques

I was first made aware of this methodology by reading Andrew Skurka’s excellent blog (if you’ve never been to his site, go poke around because the guy is an outdoors guru and it’s rightfully deserved, given the kick ass things he’s accomplished).

Dead reckoning is something many seasoned hikers probably already do without knowing it has a name. If you’ve spent any time figuring out your mile per hour pace (in varying degrees of terrain), and used it to successfully calculate how fast you might hike a route or reach the next trailhead, you’re practicing this method already.

I like to think of dead reckoning as proactive navigation, or “staying found.” If you have a general idea of

“what’s coming next,” whether it’s a landmark like a waterfall or a trail junction, and how long it will likely take to get there, you’re maintaining a general awareness of your location at all times which is invaluable information, should you find yourself “misplaced” at some point.

On my own hikes, I constantly use dead reckoning techniques and I don’t even have to think about remembering to do it anymore, since I’ve conditioned my mind to almost automatically complete the steps. Here’s how it works for me on my own hikes:

- When I start a hike or come to a trail junction or landmark, I take note of the time.

- I reference my map for the next junction or landmark to see how far away it is in miles.

- I then calculate the time I think it will take me to hike to it, based on my typical mile per hour pace, in the terrain I expect to cover.

Here’s an example: I head to Great Smoky Mountains National Park and arrive at a trailhead at 8 a.m. to hike to a waterfall 6 miles away. I typically hike about 3 miles an hour on trails in the Smokies if I’m not taking extended breaks. To cover 6 miles at a 3 mile per hour pace, it will take me about 2 hours to reach it.

If I don’t arrive to the waterfall by roughly 10 a.m. (2 hours), and I’m still not hearing water in the distance, I know it’s time to double check my map and location. Most likely my pace is just a bit slower than I estimated, but dead reckoning is a great check and balance method, to make sure you haven’t wandered off your intended route.

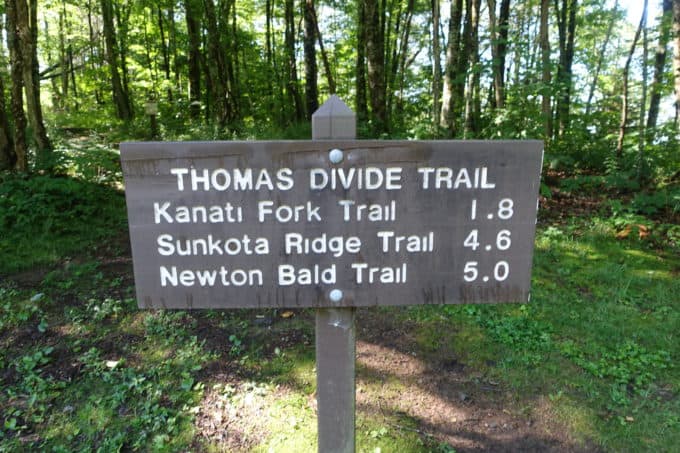

Trailhead signs in the Smokies are a great reference point for dead reckoning

Another way to think of dead reckoning is to reach back into the cobwebs of your mind to high school physics. I know, I know, you thought you’d never have to use that stuff again, right?! Well, at least it’s useful now! The formula we’re after is the following:

Distance = Rate * Time (which can be extrapolated to Time = Distance/Rate).

Using this example, I calculated the time it would take me to get to the waterfall by dividing 6 hours (distance) by 3 miles per hour (rate) which gave me an answer of 2 hours (time).

Of course things like the terrain, weather, and even the way I’m feeling that day will play into my estimated pace per hour. And be careful to give yourself a “grace period” with your estimation, so you don’t start worrying you’ve missed a trail junction or landmark if it takes you a little longer to get there than you estimated.

Figuring out your typical mile per hour pace is gleaned over time after intentionally calculating it over various hikes in different types of terrain. Your mile per hour pace can vary significantly depending on the ruggedness and steepness of the terrain you’re covering. You’ll get a general sense of it over time though, if you’re intentional about paying attention to it.

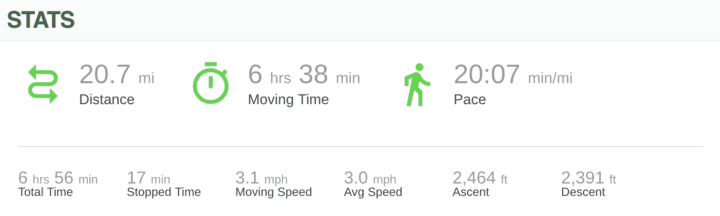

As mentioned previously, using a navigational app like Gaia provides an easy way to collect and store data over several hikes to determine your average pace. It will calculate everything from your average pace with breaks to the amount of time you only spent on the move.

This is an example of some data Gaia stored from one of my recent hikes. I can easily reference my stats over several hikes and come up with an average (or a set of averages, based on the elevation gain and loss) for my own hikes to use with dead reckoning techniques.

One final thought: Dead reckoning works best on known trails, not for off-trail exploration where your pace can vary significantly depending on the terrain and what you are walking through in regard to vegetation, geological features, etc., which is somewhat unknown until you get out there and explore it.

Key Takeaway: Dead reckoning should always be your first line of defense to getting lost on a hike. It’s one of the easiest navigational tools to learn and use on a hike, and with repeated practice it becomes second nature to use it.

Off trail dead reckoning can be a huge challenge when you’re navigating through the Smokies. (Photo compliments of Earl Tipton)

Environmental Navigation

Of all the ways to navigate, this is the one that I probably use the least on my hikes, but I enjoy learning about this method the most. It’s incredibly gratifying to learn how to sharpen my navigation skills through the stars, moon and sun, and even through plants and weather. It’s a topic I won’t delve into very deeply right now, because I think I’ve probably filled your brain with enough information to chew on for awhile.

However, if you’d like to tiptoe into the world of natural navigation, I recommend reading The Natural Navigator: The Rediscovered Art of Letting Nature Be Your Guide (Tristan Gooley). The author has written several books on the topic of natural navigation but this one is geared best towards hikers, in my opinion. He has a corresponding website that’s fun to peruse (and I enjoy his email newsletter with focused tips and tricks).

At a minimum, promise me you’ll learn how to find Polaris (the north star) by using the Big Dipper. Besides it being a useful navigationskill, you can impress your friends the next time you’re on a camping trip by teaching them too!

Conclusion

In the world of search and rescue, we routinely implement the first three techniques. We use our GPS units when we need to document coordinates (waypoints) for clues we might find. But we pull out our compasses when we need to head off trail on a certain bearing to search for someone. And finally, in addition to using it for ourselves while we search, we use dead reckoning calculations to estimate how far we think a lost hiker may have strayed from their anticipated route or “last known point” seen (there’s actually a tremendous amount of data we use to predict “lost person behavior”–it’s really fascinating). In other words, we don’t just check our minds at the trailhead; we use the navigational technique that best suits the situation.

I hope by now you understand that navigation should be approached from multiple angles and with various techniques for the greatest degree of success. But don’t let it become a tedious chore–have fun with it! It’s empowering to look at a map and be able to figure out where you are on a trail, based on the surrounding topography, or to estimate within minutes how far it will take you to travel several miles on a trail, or to make an educated guess which direction you’re facing just by looking at the vegetation around you. Navigation has become one of my favorite aspects of hiking and I hope it becomes the same for you!

Feel free to leave a comment or questions below!

Happy trails,

Nancy

P.S. I offer a “Hiking 101” series of lessons to my readers (it’s simply a labor of love and completely free). I cover all sorts of topics, but the overarching theme revolves around what search and rescue teams wish ever hiker would learn and do, to reduce the chance of needing our help. I hope you’ll consider signing up for it, if you’re interested in knowing this important information. And if you’re already signed up, just disregard this!

“Maps encourage boldness. They’re like cryptic love letters. They make anything seem possible.” ~Mark Jenkins